Teton Leads Nation in Per Capita Income

Astronomical wealth complicates life for residents of truly average means.

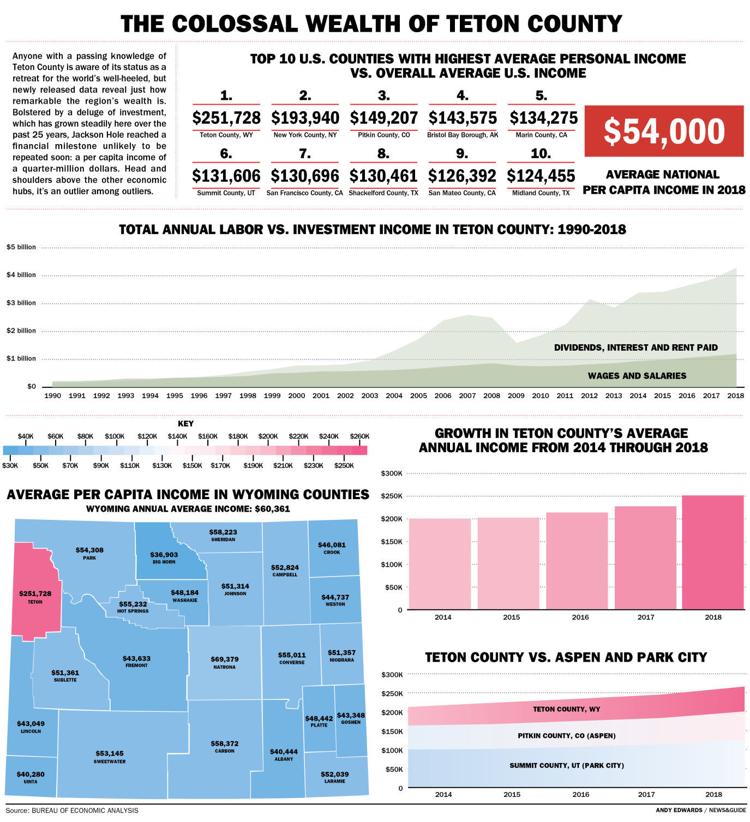

For the first time in American history, the “average” resident of a U.S. county earned more than a quarter-million dollars last year. Surprise — it’s us.

In other words, if you were to take all the income generated by Teton County’s 23,000 residents in 2018 and divide it equally among those residents (including children), each would go home with about $252,000, according to recently released data from the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis.

That may be a shock to the actual people reflected in the data, the vast majority of whom can only dream of such cash. It’s not the reality for most working people here, but rather the distorted result

of a highly concentrated inflow of investment income: money from shareholder dividends, loan interest and rent payments.

It’s no secret that Teton County, a tax haven in one of America’s most breathtaking locales, is replete with the uber-wealthy. But even so, the dollar figures that validate that — and the extreme inequality they imply — are astounding, experts say.

For years Teton County has led the country in per capita income, though “led” doesn’t do justice to the region’s meteoric rise through the economic ranks. It surpassed New York County, New York(Manhattan), in the early 2000s, and never looked back.

It would be an understatement to say the lead is secure. Today Manhattan, arguably the financial capital of the world, remains in second place at $194,000 — nearly $60,000 below Teton County.

The gap between us and the closest competition is greater than the nationwide per capita income, which is just over $54,000. Of the roughly 3,100 other counties, all but about 20 come in under$100,000.

An ‘extraordinary jump’

In 2017 and 2018 alone, per capita income in Teton County rose by nearly $24,000, more than the average of the 14 poorest counties in the country. That detail in particular struck Jonathan Schechter, a Jackson town councilor and economist, who explored the issue in a post on his blog site, CoThrive.

“It’s an extraordinary jump in one year,” he said. “It’s the biggest ever a county has had in one year.” And the trend seems likely to continue, Schechter added, considering the stock market’s exceptional performance.

That’s because the origin of that income, not just its sheer enormousness, is also unique. Look virtually anywhere in the country, and you’ll find that the main driver of local income is labor — wages and salaries earned in 9-to-5 jobs. But here, the vast majority of the money comes from investment income. That’s yet another indicator that mere financial mortals aren’t benefiting from the overall surge.

“The rush of wealth to this community has a particular source,” wrote Justin Farrell, a Yale professor, in his forthcoming sociological case study of Teton County’s moneyed class, titled “Billionaire Wilderness: The Ultra-Wealthy and the Remaking of the American West.”

“It was not the result of broad-based economic growth or rising wages and salaries,” Farrell went on, “but was gains from one particular sector of the economy.”

The swell of investment is a fairly recent phenomenon. Labor income historically came out on top until the mid-1990s, when investment soared ahead. It dipped during the recession, but is again climbing to historic heights, reaching nearly 75 percent of total income last year.

Interestingly, the rest of Wyoming doesn’t seem to share the same appeal to the wealthiest classes. The per capita income in most other counties ranges from $40,000 to $50,000, and none are above $70,000.

“Teton County is, for better or worse, an outlier,” said Rob Godby, an economist at the University of Wyoming. “It’s a very different set of problems.”

Inequality on the rise

One consequence of Teton County’s extraordinary income is an equally extraordinary income inequality, also the greatest in the country.

The quarter-million statistic, and its investment underpinning, is all the more impressive considering that a large proportion of wage and salary jobs here are relatively low-paying tourism gigs.

“Jackson is potentially a tale of two towns,” Godby said. “You have the very wealthy, and then you have the incomes that maybe look more normal.”

Of course, the normal-income demographic is far more populous. According to Internal Revenue Service data from 2017, just under 1,900 households reported an adjusted gross income of $200,000 or more, the highest bracket. That’s about 13 percent of the 14,400 households in the county.

“You can tell a lot by looking at that distribution of income,” said Jeff Newman, one of the economists who put together the income report for the Bureau of Economic Analysis, which is based on income tax data. “You can really get a good feel for an area.”

For the 87% earning less than $200,000, and especially for those on the lower end of the spectrum, the costs of living in Teton County are daunting.

The most obvious effect is on housing. With property in such short supply — 97% of the county is public land — there simply isn’t nearly enough to cheaply accommodate the worldwide desire to live in and visit Jackson Hole.

What little land is available is often accessible only to the upper middle class and above. In short, most incomes are not keeping pace with mounting housing prices.

“The most basic law of economics is supply and demand,” Schechter said. “If you have a high demand and low supply, the pressure’s going to be pretty high.”

After housing, the secondary effects are many. Despite the community goal to house 65% of local workers, about 40% are forced to live elsewhere and must commute. That increases traffic and carbon emissions, alters the character of neighborhoods and, overall, lowers quality of life.

Many of the people most fundamental to community, from teachers to snowplow drivers to law enforcement officials, can barely afford to live and work here. Last month Teton County Sheriff Matt Carr warned that the communications center is one dispatcher away from being unable to respond to 911 calls 24/7.

Teton County isn’t alone in these struggles. They’re hallmarks of the most popular tourist destinations, and especially of premiere mountain ski towns: Pitkin County, Colorado (home to Aspen), is third on the list of per capita income, after Manhattan, and Summit County, Utah (home to Park City), isn’t far behind.

The subject of income inequality doesn’t often come up in community dialogue — except perhaps through the proxy of housing — but it does feature prominently in a recent report that elected officials are consulting as they update the Comprehensive Plan.

Based on input from hundreds of residents, the Comprehensive Plan review stresses that the public is concerned about inequality, yet the town and county’s guiding document never explicitly mentions it.

“If the community does not define how it wants to address income inequality,” the report states, “the inequality will define the community.”

Schechter said “there are very few unadulterated goods and very few unadulterated bads.” The same economic forces that have made it such a challenge to live here have also made it a remarkable place to live.

“It’s a testament to the work a lot of people have done to create an environment where people of such wealth would want to come,” he said.

Without that wealth Teton County certainly wouldn’t be the community it is today. The nonprofits, the school system, the pathways, the restaurants, the conservation — many of the most cherished aspects of Jackson Hole depend on the immense stream of investment income running through it. These amenities require a financial sacrifice.

“What Teton County is,” Godby said, “is a blessing and a curse.”

In fact, he said, people consciously or unconsciously make a trade-off when they decide to move here. Research shows that many in Teton County are willing to accept a lower income than the cost of living would suggest — likely because of the superb access to wilderness and the other aforementioned benefits.

That doesn’t change the fact that the cost of living is often overwhelming, and Godby said it’s still worth striving to alleviate the hardships residents face.

“There should always be a healthy conversation about the limits of what’s acceptable in terms of social welfare,” he said. “Putting it in blunt terms: the health of the community and what people are willing to do — how much they care about their neighbors.”

As for the affluent of Teton County, surely they do their part in attempting to fix what’s broken here through charity. But, as outlined in the News&Guide’s Imprint edition on the impact of philanthropy earlier this month, their donations don’t always align with actual needs.

While working on his book, Farrell spoke to a Mexican immigrant living in the area: “He wonders aloud whether wealthy people care more about saving a moose or a bear than helping him and other immigrants who are suffering.”

People like him “are seeing more clearly how these same friends who have so much extra money and power to help nevertheless support the status quo and perpetuate a system that is making it increasingly difficult for [him] and his family to live a decent life.”

Whether Teton County will ever solve — or even adequately remedy — its lack of affordability remains to be seen. Schechter observed that many other communities have buckled under the same pressures, and none have yet found a way to pick themselves up, particularly not while also trying to protect the surrounding ecosystem.

It may be impossible to tame housing prices enough that they become widely available to those of truly average income. Even if it becomes easier to live here, Godby said, more people will want to live here.

Yet making the effort is paramount, Schechter said. The alternative is unthinkable.

“If we let it go down that path,” he said, “we are going to become a community where very few nonwealthy people can live.”